This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site you are agreeing to our use of cookies. Read our privacy policy

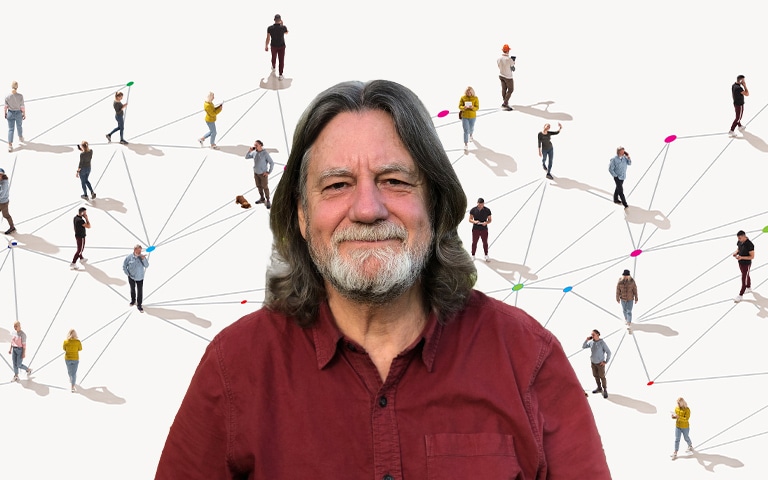

Tech can either bring people together or widen the gap between them, says world-renowned economist Jeffrey Sachs.

Professor Jeffrey Sachs is Director of the Center for Sustainable Development at Columbia University, and President of the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network. Here, he tells Huawei Editor-in-Chief Gavin Allen how AI and connectivity could end poverty and save the planet – if society mobilizes the right resources.

GAVIN:

In a speech you gave last year at a Huawei sustainability event, you said that “digital technologies are absolutely key to the transformation of our economies in a way that could produce the end of poverty and the end of environmental destruction.”

How will technology help achieve those ends?

JEFFREY:

Advanced digital technologies will play a breakthrough role in raising productivity in every sector of the economy, and hence can be key in accelerating the end of poverty. Digital technologies will enable precision agriculture that raises farm yields with lower inputs of land, labor, fertilizers and water. Digital technologies will enable autonomous mining, to end the backbreaking and dangerous work of underground mining. Digital technologies will empower high-tech assembly lines even in low-wage and relatively low-skilled settings.

Digital technologies are already revolutionizing retail trade and retail payments systems. Digital technologies enable online education where highly trained teachers are scarce, and online healthcare where radiologists, laboratory technicians, and clinicians are scarce. Digital technologies can obviously support real-time language translation and interpretation in places with multiple native languages. Digital technologies enable low-cost smart power grids and maintenance of infrastructure. Digital technologies enable universal online biometric identification for use in both public and private services.

Of course, if the digital divide widens, ICT can also exacerbate inequalities and leave the weaker, poorer, less educated parts of society even further behind. The key is to ensure universal access to the skills and digital platforms needed across the society.

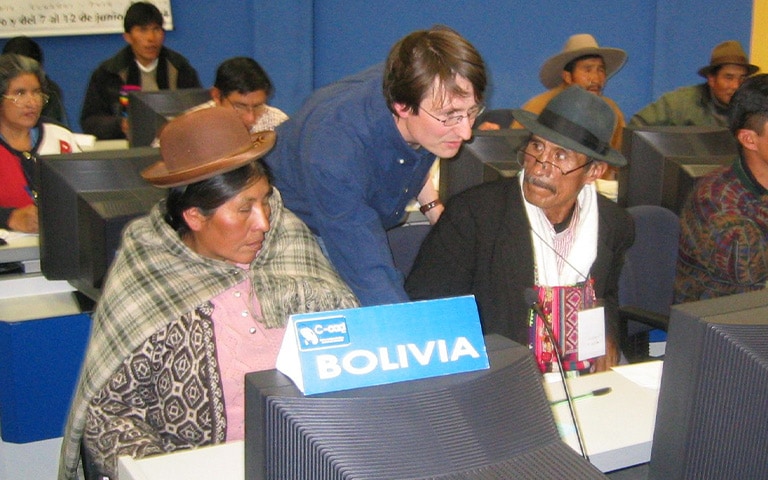

The main challenges to achieving universal access include the following: (1) a national investment strategy to ensure universal physical coverage of high-quality broadband; (2) a national pricing and financing policy to ensure affordability (and subsidization as needed) for universal household access to data and devices; (3) the incorporation of digital services into publicly provided healthcare, education, banking, payments, and public-sector taxes and transfers; (4) training of the public to use advanced digital services and devices; and (5) training of young labor-force entrants to utilize, adapt, and innovate along the entire digital supply chain.

These are indeed huge public-sector challenges, especially in low-income settings, but they are also priorities for successful sustainable development of all countries, with special benefits and opportunities for the poorest countries to leapfrog in infrastructure services and public social services. China and India have clearly shown the enormous benefits to long-term growth that can be achieved by incorporating digital services into public investment strategies.

GAVIN:

At COP28 in Dubai, I spoke with the former Nobel Peace Prize winner Prof Mohan Munasinghe about climate justice. As he framed it, it’s rich countries pollute the environment while poor countries pay the price. In the interest of fairness, he therefore argued, there should be a financial rebalancing.

Can a similar argument be made for “digital justice”? A good connection lets you go to school, see a doctor, learn new skills, and expand your professional network. Shouldn’t everyone get those benefits, even those who happen to be living in poor or remote parts of the world? And if this helps combat mass economic emigration, then isn’t it not just a duty, but in the self-interests of richer nations to help fund that connectivity in poorer nations?

JEFFREY:

Every country should work with its telecoms and tech partners, such as Huawei, to develop a national strategy for universal coverage and access to online services. Such a strategy will entail a mix of public and private investments. The public investments will in turn depend on access to low-cost long-term financing, such as from the Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) and initiatives such as the Belt-and-Road Initiative. Governments cannot do this on their own. They need to work with the UN agencies (UNESCO, ITU, UNICEF, WHO, FAO), specialized institutions (such as the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria), the MDBs, and the tech companies to put these strategies into operation.

GAVIN:

In many poorer countries, putting base stations within reach of people in remote areas can be expensive. It can take more than 10 years for operators to break even.

How much should ICT companies be thinking about how to address this challenge? Is it reasonable to expect companies to sacrifice profits for the greater good – and if so, how much sacrifice do you think might be required?

JEFFREY:

There are several solutions. First, ICT companies can help governments design the lowest-cost solutions. Second, the Multilateral Development Banks can help finance the rollout of physical infrastructure and digital platforms with long-term, low-interest loans. Third, creative payment plans can help low-income countries gain access, even if it’s somewhat limited at the start, for non-essential applications. Fourth, digital public services in healthcare, education, and public administration should be incorporated directly into national budgets. Fifth, and generally, the global financial architecture needs basic reforms to ensure that even low-income countries have the long-term financing they need to achieve the SDGs, including the rollout of digital services with universal access.

GAVIN:

To what extent should governments focus on helping ICT companies do the right thing – for example, by creating tax breaks or other incentives that would encourage the private sector to expand and enhance connectivity everywhere?

JEFFREY:

Generally, governments and ICT companies should come up with joint financing plans that include a blend of private financing and official financing, such as through the Multilateral Development Banks.

GAVIN:

When we think about the future, would it be more ethical to focus less on the AI-enabled tech jobs, products, and applications that will make most educated people's lives significantly better, and instead, focus more on protecting the less skilled people who are so often structurally disadvantaged by those tech advances, particularly in developing regions?

JEFFREY:

It is certainly true that all or almost all decent jobs of the future will depend on quality education and excellent skills that work effectively alongside the new digital technologies. Every country therefore needs to ensure universal quality education as its highest national priority. This of course also requires universal digital access. I think the AI-inspired focus should be on achieving universal quality education, universal quality healthcare (e.g., through telemedicine, remote monitoring, digitally empowered health workers), online payments, etc. The jobs-skills issue should be handled mainly on the supply side (ensuring well-trained workers) rather than by trying to design digital technologies to create new jobs. The jobs will come alongside the skills.

GAVIN:

In your most recent book, you talk with religious scholars and philosophers about sustainability. Do we need the same approach to AI – striving for the widest consultation possible, in order to ensure that AI research and deployment is conducted to benefit humanity, not harm it? And should the old medical mantra of "First, do no harm" be the baseline control placed on AI's human creators?

JEFFREY:

All advanced technologies are two-sided: they can improve well-being, or harm it. Every technology should be monitored and governed to restrain its dangerous sides. In that regard, AI is no different from nuclear technology, advanced biotechnology, energy technologies, etc.

Many of AI’s risks have been identified, including autonomous AI-empowered weapons; various kinds of social biases built into AI algorithms; loss of privacy; loss of human control over digital systems; addiction and other mental disorders from misuse or overuse of digital technologies; deep fakes; enhanced government propaganda; hidden censorship; and other risks. The UN, with the support of China, the US, the EU, and others, should take the lead in proposing strategies for oversight, transparency, and regulation of these potentially risky dimensions of AI.

GAVIN:

One recent contributor to Transform said the real key to positive and sustainable AI development is education, so that people are fully aware of the opportunities and challenges when they engage with the technology. Do we need to accelerate tech teaching globally? If so, how might we go about it?

JEFFREY:

Education is an important part of the story to be sure. It is not enough, since many companies are hiding what they are doing, and certainly the US government hides many of its AI applications for surveillance and military uses.

As for education, the good news is that digital awareness and digital skills can also be taught substantially online. As universal physical coverage and data access are achieved, there must indeed be a plan for three kinds of public education: (1) on the practical uses of digital systems and platforms; (2) on the innovation of digital platforms (for software engineers and other technical workers); and (3) on the kinds of risks and dangers of the new technologies that need to be understood, publicly discussed, and regulated where necessary.

GAVIN:

Is technological development the secret future antidote to warfare? Or – without globally sustainable development and a more balanced approach between rich and poor - is it more likely to cement existing divisions (as the geopolitics expert Ian Bremmer put it: "Technology gives you more of what you already have")?

JEFFREY:

In a recent lecture (the Iqbal Lecture at Oxford University, here), I outlined three distinct kinds of wars. The first is wars of competition between two or more major powers. These could be called wars of hegemony, like WWI and WWII. The second is war between the powerful and weak, as in imperial conquests. The third is civil war among social groups, e.g., different religions, languages, cultures, races, classes, and/or regions, within a nation.

Alas, AI could spark all three kinds of wars, but in different ways. AI is accelerating the arms race among the major powers. AI is widening the gap between the powerful and the powerless. AI and digital media are promoting rumors, fake news, and the spread of hatred. In short, the disruption from AI will not end war, but could exacerbate many potential or actual conflicts. We must solve these conflicts through dialogue, negotiation, pursuit of common interests, adherence to the UN Charter and international law, and the design and adoption of new international laws regarding AI and digital technologies as may be needed.

Contact us! transform@huawei.com