This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site you are agreeing to our use of cookies. Read our privacy policy

Bianca Reisdorf is Associate Professor, Dept. of Communication at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte

These days, it seems the Internet is ubiquitous and everyone’s got a smartphone. So, plenty of people feel that the Digital Divide is a problem that’s already been solved. What would you say to someone who feels that way?

I hear that a lot as part of my research. Those of us who are well connected don't even think about issues like aging devices, data caps, not being able to pay your internet bill, having slow and/or intermittent access, and so on. Everyone seems to be on their phones all the time, so there really shouldn't be a problem.

But for a lot of people, especially in highly technology-dependent countries, the problem isn’t necessarily the lack of a device or an internet connection. It’s a lack of fast, reliable access – to the internet, and to various different, and up-to-date, devices.

Dr. Amy Gonzales coined the term "technology maintenance," which refers to the ability to maintain devices and internet connections in a way that allows full participation in the digital world. A lot of people don't have the means to do that. So, rather than being completely unconnected, they are what Dr. Vikki Katz refers to as “underconnected.” That’s a huge problem, as it affects how well people can reap the benefits of the online world.

So even though in much of the world, anyone who needs a cell phone can get one... But just having a mobile connection to the internet does not, by itself, equal “digital inclusion.” Can you expand on that?

We like to think that having a cell phone will solve the issue of digital inequity. But relying on mobile access alone leads to engagement with fewer online activities.

In a study I conducted with several colleagues at Michigan State University, we found that those who had internet service at home in addition to their cell phone participated in a significantly larger range of online activities, many of which are considered "capital-enhancing."

That means they allow people to increase their financial or economic capital, for example by saving money online, or getting an online education. It can help people build social capital in the form of better, more numerous social connections.

When people have to choose between a mobile connection versus one in the home, most will choose the mobile connection because it's more flexible. But overall, the mobile connection doesn't afford the same range of uses that a laptop or desktop computer would.

I hear this a lot in my qualitative research projects: people are struggling to fill in job applications or government forms on their cell phones. They try to supplement their mobile access with access at the library, or at a relative's or friend's house. But nothing beats having your own devices and having stable, fast internet access in your home.

Which recommendations do you offer policymakers who want to improve the current situation?

Digital inequity is a moving target. There is no one-time fix that will permanently solve the digital divide, as new innovations, devices, gadgets, and faster internet connections become available all the time.

So, when we have great policy interventions, such as the Affordable Connectivity Program (ACP) in the U.S. – which is, unfortunately, slated to run out of funding this spring – we need to build on these helpful policies, rather than running them for a time, then stopping, which just means that a lot of people will again lose reliable internet access.

Programs need to be designed in a way that is sustainable and also adaptable to the changing digital landscape. One-off programs are great at alleviating immediate needs, but the reality is that devices get older and eventually become unusable, and internet bills have to be paid monthly, so temporary financial support also just means temporary relief.

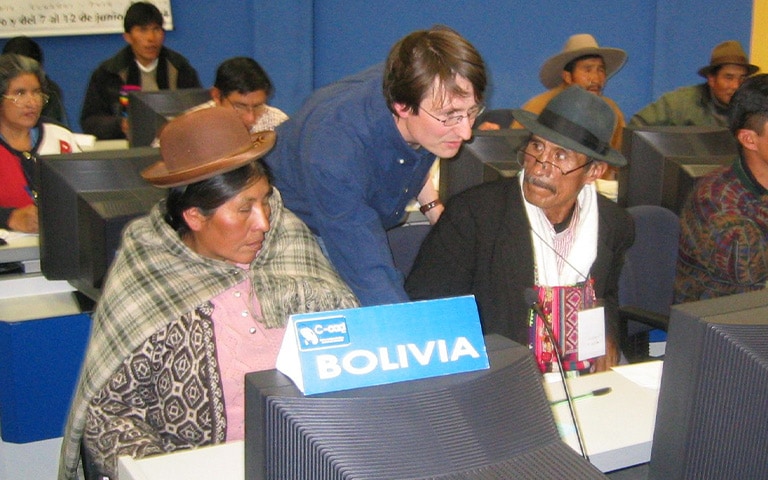

Sustainable programs need to be designed together with the communities that they are trying to serve. What might work in New York City may not work in rural Pennsylvania, and what might work in Shenzhen may not work in Hunan.

Besides people living in communities of concentrated disadvantage, you have also looked into other vulnerable groups, such as people who are returning to society after serving time in prison. Nowadays, many basic tasks have migrated online: finding a job, finding a place to live, and so on. I would imagine that this is a great challenge for people who have been incarcerated for 10 years or even longer. How can we address this issue?

It doesn't even have to be a long prison term. Even people who served comparatively shorter sentences, such as three to five years, still experience a huge culture shock when they return to our digital society. I've heard stories about missed job opportunities simply because someone wasn't able to use a computer, or didn't have an email address, or was unable to check their emails for a week because they couldn't pay their cell phone bill.

It's counterproductive to simply lock people up and then release them back into a completely changed society without giving them the tools to succeed in that environment.

At a minimum, returning citizens all should have access to, and be taught to use things like computers, cell phones, and the internet. This will help them handle crucial tasks such as finding housing, applying for a job, getting directions, producing resumes and cover letters, learning proper email and social media etiquette, and so on. Without these skills, we're setting people up to fail.

What do you think can we learn from your research for the wider context of digital inclusion and especially the role that digital technologies play for alleviating poverty?

Digital technologies and the internet are necessary for participating in our technology-dependent societies, but they are not the solution to alleviating poverty.

Not having (the same quality of) digital access exacerbates poverty and inequity, but we need to move away from the idea that technologies can solve a social issue, such as poverty and inequality. Policies addressing digital inequality need to go hand-in-hand with policies that directly aim to address social inequality and poverty to be successful.

We can think about it like this: A boat could have the best and fastest engine, but if the hull has a hole, it will still sink. Similarly, trying to fix a social problem by throwing shiny new technology at it will not address the root of the problem, and such policy solutions are bound to fail.

Contact us! transform@huawei.com